My grandfather was the kind of patriarch who lives in a world that everyone knows is actually run by women. To my great satisfaction and intense envy, I knew from a young age that the stoic brown women around me were the ones who kept us fed, clothed, and comforted in a narrative blanket of gossip, advice, and emotional continuity, tolerating our foibles and first-generation immigrant chaos out of a kind of self-renunciatory love. I adored my grandmother, with whom I spent much of my childhood in a silent woman’s language of co-presence interrupted only occasionally by a quick phrase in Punjabi. My grandfather, by contrast, struck me as eccentric in his dogged belief that he was the head of the family despite my estimation that between my grandmother and mother—who ran our household better than any man ever could— men were obviously not capable enough to be in charge.

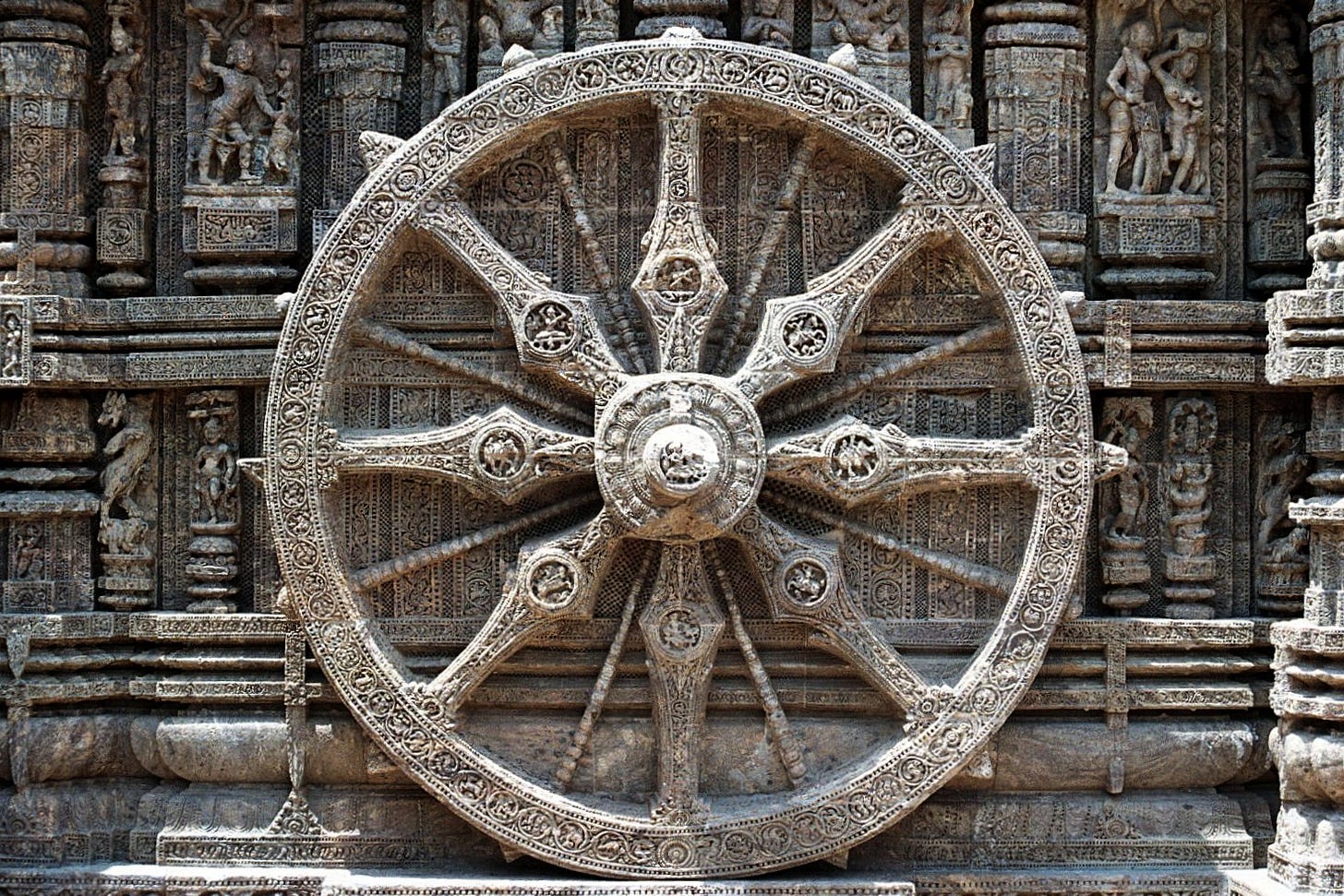

Maybe for that same reason, I found my grandfather’s teachings fascinating. He was full of the kind of diasporic bravado and masochism that made brown masculinity palatable to the British Empire that ruled over us, asking us grandkids to walk on his back to relieve pain from years of manual labor, or extolling the virtues of finishing your plate of roti and dal as fast as possible at lunch despite the indigestion it would bring. There are two parables of his that have never faded. I can remember him calling me into the bathroom one day while he was cleaning the toilet. Scrubbing intensely, he explained to me that Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the patriots who freed India from the British, taught him that men and women both had to do housework to be free. This was, I gather, his lesson to me in nationalist feminism: swaraj (homerule), the principle of Indian nationalist sovereignty, was a clever analogy to literal home-rule, the harmony of a modern, feminist household where men and women shared in labor. This was especially resonant for Sikhs like my family, where religion dictated that women and men be formally equal in most practical matters (with all the drawbacks of merely formal equality). My grandfather told me to squint at the toilet bowl and see in its circular shape the Dharma Chakra of the Indian flag. A toilet bowl was an absurd metaphor for decolonization, but that’s probably why I still remember it.

The other parable was much simpler. My grandfather refused, stubbornly and for decades until close to his death, to sell our family land back in India. It was relatively worthless farmland and, what’s more, entirely unstaffed now that our family was established in Canada. But his rationale was unchanging: “We have to keep the land because you never know when the white people here will send us back.”

This lesson in the brute power of colonialism stuck with me, making my eventual education in Frantz Fanon’s anti-colonial thought in college something like the confirmation of an underthought hunch. I had long understood that land belongs to no one; just because you purchase some in Canada doesn’t mean the white descendants of the same British who ruled over Punjab couldn’t politically evict you one day. As I’ve come to understand Canada’s own insidious form of settler colonialism, I’ve found it fitting how much depth forms in my grandfather’s sentiment. We don’t belong in Canada in the first place, us settlers, so our refusal to buy into the fantasy of property, or land as the guarantor of security from racial violence, makes all the more sense.

I think a lot about how my primary exposure to racism, colorism and anti-colonial pedagogy primed me to be brown and trans in the world. What I mean is, no one gave me a language, concept, or framework to make sense of my growing dread at being raised a boy when I was young, but I was handed many lessons in how to navigate the differences of my brown skin, my family’s language, culture, and religion, and so I adapted them to understand gender as any kid ill-equipped for the world would. My grandfather’s stubborn refusal to see immigration as anything but a pyrrhic victory in a world formed of colonialism imprinted in me a sixth sense I still trust today.

There’s a difference between sensing crisis in the collapse of a world’s order, like the British Empire, or seeing India and Canada—two nominally “free” democracies—as organs in the same unfinished project of colonization, the theft of land and the extraction of value from the poor, brown masses. This is something like the primary trans of color lens through which I’ve tried, in recent months, to make sense of the anti-trans crescendo through which we are living in the Anglo-American metropole.

I’ve described my entry into media punditry and online writing on trans issues to friends as “reluctant.” I’m an immigrant to the US myself and can’t vote, so what business do I really have commenting on legislative efforts in states I don’t live in? Well, I guess I sort of wrote the book on trans kids, so drafted I was. I’m proud of being able to make some use of my unusually broad and deep knowledge about trans childhood and the historical roots of today’s crises to speak to a broader, nonacademic audience. But I really hadn’t expected to write what I’m now affectionately calling a trilogy on anti-transness and state power:

1. “The Cis State,” from a few weeks ago here on Sad Brown Girl, which details how anti-trans bills are part of an effort by the state to declare it has an official cis gender and, therefore, a legitimate interest in disenfranchising trans, nonbinary, and intersex people.

2. “The Anti-Trans Lobby’s Real Agenda,” at Jewish Currents, which dissects the Evangelical Christian play to exploit the inherent weaknesses in American secularism and build a Christian ethnostate via anti-trans legislation.

3. And “From Gender Critical to Qanon,” forthcoming soon at The New Inquiry: an essay that details how respectable anti-trans punditry (think the Lisa Littman to Abigail Shrier pipeline) plays the important role of laundering anti-trans extremism and conspiracy theory from radical right-wing groups so that it can be made palatable enough for GOP legislating in places like Texas.

While each of these pieces analyzes the political strategy of the right, my critiques in them have been uniformly directed at the left, which I find exasperatingly unable to reckon with the profundity of anti-transness in cementing the rise of authoritarian political movements and the white racial politics fueling attacks on democracy. We have been had in agreeing to the right’s bad faith arguments and “debates” over narrow trans hypotheses. We are distracted from what anti-transness aims to accomplish in the outcome, regardless of motive, truth-value, or tone. We have failed to see the scale at which anti-transness as an anchor of political power moves.

And so, I feel torn, watching our collective sigh of relief, say, in Texas, where yet another anti-trans bill died yesterday at midnight when the legislature’s clock ran out. Social media tells me we have successfully defeated every single anti-trans bill in Texas during this legislative session, which ends in five days, freeing us to…wait until the next session, presumably?

(I hear a faint echo of an old Marx quote in my head: “The oppressed are allowed once every few years to decide which particular representatives of the oppressing class are to represent and repress them.”)

These are pyrrhic victories in the sense that in winning on narrow terms, we unwittingly validate the attack in the first place, normalizing it precisely because it could not survive the legal process, which makes us fantasize that the corrupt legal process is actually legitimate. Before you think I’m being petty or overly pessimistic, think of the material damage done by spending months vilifying trans youth and seeing them dragged through the national and local media, subject to horrifying attempts at extinguishing their lives, and becoming the center of any number of fascist libidinal fantasies about “saving the children” by abusing them openly and shamelessly. It doesn’t matter, in a certain sense, that the bills were defeated, the damage is done. I didn’t come out as trans in high school because I judged it far too dangerous. But I truly can’t fathom surviving with the kind of target painted on the backs of trans kids today, especially girls. The sheer lust for blood on the part of transphobes, who are content if not thrilled to watch an entire class of human beings libeled into treatment as enemies of the state, is chilling.

I have no doubt my grandfather’s clumsy feminism forged in the nationalist fight against British colonialism would stumble, were he still alive, on my transness. But I have no taste for sacrificing real life for ideals. His anti-colonial lesson is stuck in my head these days more than usual: we have no land to stand on, not simply because liberal state power and its racial unconscious have taken it from us, but because we were never meant to believe in land in the first place. We must learn to build life, safety, durability, and freedom without the false gods of property, individualism, civil rights and liberal citizenship, for those ills cannot heal the disease they have produced.

Otherwise, we will be doomed to defeat bill after bill, year after year, while we find the zealous protection of our legal principle has done nothing to save us from the flood of material violence engulfing our flesh and blood, our hearts and souls.

Hell yea