THE POSTCOLONIAL CONDITION can sometimes feel like the astounding letdown of having willfully become better at everything than your jailer, only to be confronted with his essential mediocrity—and all a little too late to take it back, like a joke you can’t undo after it’s bombed.

The last place I found myself before I started estrogen was New Delhi. The cheap pleasures of a Western hotel chain’s shiny new development would have normally struck me, who grew up in the tawdry 1990s suburbs of the diaspora, as embarrassing, except for the fact that this lazy capitalist fantasy of cosmopolitan India was my deliverance from a month of asphyxiation in the quintessentially provincial province of Punjab. Like a Rupi Kaur poem that had stared in the mirror for too long, becoming horrifyingly self-aware, my family and I had dutifully returned to our village only to be reminded that no one in our family lived there anymore. Confronted with the visual decay of a world literally emptied out by immigration, leaving behind crumbling houses and farms tended by exploited rentiers, we were warned that the area had descended into drug-fueled brawls and shoot-outs. I had my doubts as to how true those specifics were, but I believed the general outline of the story.

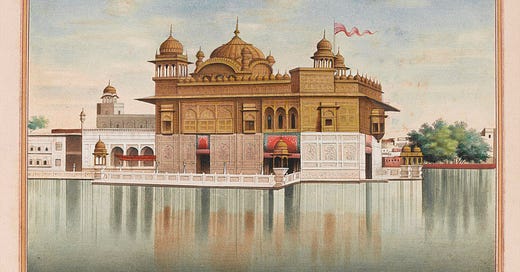

My sister and I spent an especially absurd night in gender-segregated dorms at the most sacred site of Sikhism, the Golden Temple at Amritsar, angrily cursing our bad luck at being born into the one subcontinental religion without a sacred third gender. Clad as we were, so obviously wrongly, in kurta over the previous few weeks, we were exhausted from the constant surveillance of our misfitry. Whenever we would stop at a distant family friend’s home and sit for tea, it was inevitably under the eyes of older women who, having prepared themselves to tolerate what happens to the children of immigrants, couldn’t contain their shock at just how far things had apparently gone over there in the West.

Earlier that evening I had found a wifi hotspot long enough to get the news that my book of transgender history had been nominated for a Lambda literary award. When we arrived at the temple floor and sat cross-legged, my linen pants ripped at the crotch, bathing me in a shame so searing it surely could be heard over the prayers on the loudspeakers.

That I couldn’t square the coincidence of these events, trans and brown, was hardly news to me. If anything, I had been exceptionally lucky to be born to my mother, the dashing apostate who became a feminist in the 1980s, married a white man—and later divorced him—and had queer children. I grew up singing Madonna songs with her in the car. We were long marked by our common lack of Punjabi normativity and she had never made me to feel badly for it. If anything, she helped me understand it wasn’t my fault we were treated differently. But to my great disappointment, the world was not coincident with my mother, and so I began to find comfort in thinking of the situation as historical, rather than personal. That’s why I had wanted to become a historian in the first place. I had taken a class in college with an absurdly brilliant professor born into a high caste, then educated at Oxford and the University of Chicago, who introduced me to the postcolonial school of Marxist Indian historians. I learned then the kind of gripping possibility of postcoloniality as a revenge plot: Indians had taken the discipline of history and perfected it, as if to once and for all sneer at the British with their imperial fantasies of a centuries-long Raj by making sure that no one could ever again think of such world-historical vanity projects the same way.

It was the self-flagellating postcolonial revenge plot I had encountered so many times as a 1990s model minority kid in Canada: don’t resent them for their many and ongoing crimes, just become so much better than them that they will have to recognize your goodness one day.

Whatever youthful hope I had first cultivated at the idea that I could outclass the fools whose British Empire had produced me as its queer byproduct were laid to shame that evening in Amritsar as I was reminded just how useless my now award-nominated book of history was to me. It was like how, after a month of practice, my Punjabi finally clicked back into fluency, but the first conversation I had was with our family friend, him interrogating me about why I was unmarried.

I HAD BEEN to India once before, alone when I was nineteen. I went during the summer, which every one of my relatives who had lived there warned me was a foolish idea. I took the admonition on as a badge of honor, an endorsement of my impossible need to do things wrong but better than convention dictated.

I had saved up enough money working during the school year to get myself to New Delhi and, with the help of relatives, catch a bus to Punjab, where a 1960s modernist university built on the style of LeCorbusier’s concrete utopias would host me for two months while I improved my language skills. My clumsiness in Punjabi had been a constant since childhood, marking me as mixed race as much as queer in my mind. When my grandmother was still living, we had found an intimacy that verged on fluency, but it had always felt like our secret language, the domestic language of women, and one that couldn’t outlive her after she passed. Massively neurotic in college and bored after getting good enough at French, I thought I could once again up the ante and emerge poetic in my mother’s mother tongue.

It didn’t work. When I got to Punjab I found that, much like back in Canada, the campus was empty for the summer under the oppressive sun. There was no one else in my dorm building but spiders and little lizards. I had de facto private lessons for only a few hours a day and found that I was too afraid to leave the gates of the campus and travel into town afterwards. It wasn’t so much a cultural barrier as it was a ubiquitous problem: I felt scared and inhibited everywhere in my life. Mine was a self-tortured existence where the great feats of determination and concentration that made me want to become a historian, or fluent in four languages, flourished to the inverse degree that they emptied me of a self. Rather than cash in on what would surely have been a lethal dose of self-loathing, I did something I thought was smart: I externalized my vitriol for myself into sheer accomplishment, until I could make a list of all the reasons people thought I was good and so conclude that I ought to keep on living. They demanded it, after all.

Like most of my overly ambitious ventures, when the pressure of this summer study scheme became too much I decidedly rashly to quit. I called my mother, who called my uncle, who had some non-blood relative come fetch me and take me to his family home.

It was the only time in my life I experienced male homosociality, which made me feel ashamed because I already felt like an impostor, the summer school dropout from Canada that needed to be entertained for a few weeks. I had never not been read as a faggot before and was shocked to find that the drugs of respectability politics and hospitality were so strong that the men I was spending time with assumed I was one too. My “cousin,” who bore the same name as my mother (and aunt; Sikh names in Punjabi are ungendered, as if intended to taunt me), annoyed me to no end as the destructive emblem of over-coddled brown masculinity that grows in response to the infantilization of empire. Waiting endless years for his immigrant visa to Canada to come through, he worked in an auto repair shop and drank in the evenings, far too old to be unmarried, and yet. One night as we drank Scotch alone in his car, he asked me if I had ever had sex with a woman, letting slip that he had not. I lied and said yes, sheepishly enjoying the power it granted me over him, as if knowing something he didn’t could be other than alienating.

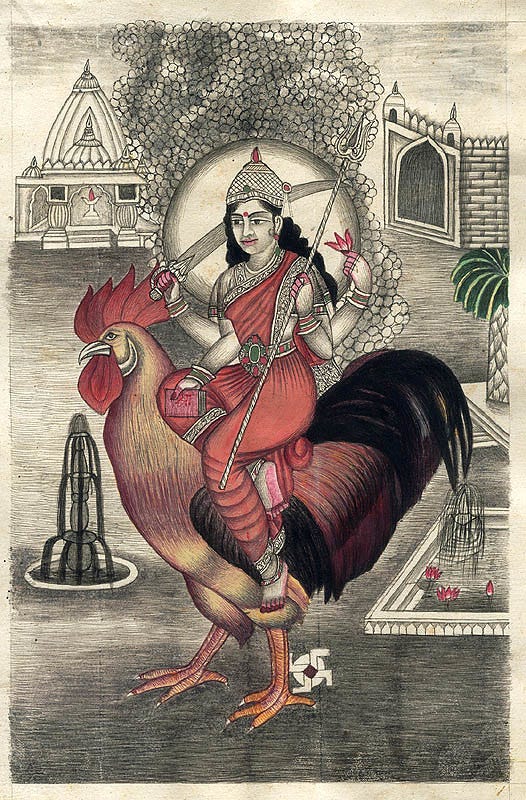

I developed a shuddering crush on his friend Lakhi (pronounced like lucky), a clean-shaven boy not much older than me who was doing a master’s degree in English literature. We devised a deal in which I would practice Punjabi with him for a day, then him English with me the next. He took me on motorcycle rides into the country to visit various Sikh, Sufi Muslim, and Hindu sacred sites, patiently explaining their intricacies and histories to my ravenous mind. He enjoyed getting a little drunk too, but without the overcommitment of my cousin, and we frequently fell asleep in bed together after a night out. This was unremarkable, as I learned through my undercover role in homosociality, but it was monsoon season and as I lay awake in the middle of the night, watching vaporous mist climb into the bedroom from the symphonic rain outside, I imagined that Lakhi and I needed no concept to enjoy our intimacy. Instead of perverse innocence born of a gender segregated system in which queer desire had its own secretive grammars, we had nothing at all, and it was freeing. I fantasized that I was simply feeling what was there, and real, and nothing more.

I had always wanted a literal experience, having lived with a corrosive meta-narrative in my head for as long as I could remember. But I lost the moment in deep guilt at the optics: brown girl trapped in brown boy’s body treats browner boy like just another colonial prop for her fantasy that she is, after all, somebody.

SOMETIMES I WATCH quietly as people opine how important it is to listen to trans people of color, for the benefit of their white awareness, and then they perversely over-applaud a trust fund influencer born of a high caste as if they were today’s nineteenth century pauper in Bombay.

Sometimes I pause in disgust and underserved astonishment, before clicking delete on harassing comments left on my published work, at the intensely angry version of troll who takes pleasure in screaming at me that I’m white, whereas most are content merely to misgender me or imagine my violent death out loud.

Sometimes, after I’ve been trying to filter out the seething rage in my bones, like a toxin that can never be fully flushed, I think about how dumb the postcolonial revenge plot is. I was born in the White Dominion of Canada and my people aren’t the ones that include Hijras and I’m a good historian without being the best and I started taking estrogen at the first appointment possible after my plane from New Delhi landed in Philadelphia.

I can admit, in those moments, that revenge is useless other than as a plot. It doesn’t do anything but extend the hurt that it is trying to denounce by making a narrative for its persistence. But there’s something less satisfying about leaving the waters muddied, plotless. Whenever I feel like I alone am expected turn the other cheek, a little bit of me threatens to die inside if I don’t take my revenge.

It’s like how, at a roadside fair on the outskirts of Amritsar, my aunt and I decided on a whim to see an astrologer. He read her palm first, noting that she seemed a stoic woman who had suffered greatly in sacrificing herself for others—particularly men. It made her cry. When he grabbed my palm next and started with the standard assessments of my lifeline, I could understand his slow spoken Hindi well enough to follow. But then his speech quickened and he went on animatedly, too fast for me to follow. My aunt, who spoke Hindi, conspicuously stopped translating, her recently-soft expression hardening into glass.

After the reading had ended and we were walking away, she asked me if I had understood what the astrologer said, to which I replied no, he spoke too fast. She recited the words as plainly as possible: “he said your energy was neither male, nor female.”

I grinned in the moment, finding it hilarious in context. But later I felt sad in a familiar way.

This hits different less than 24 hours after coming back from India 🥲🥲