Welcome to 2022 on Sad Brown Girl. I’ll be bringing you more regular snippets from a book I’m writing on the history of trans misogyny and trans femininity. Thank you, as always, for reading.

-Jules

There are impolitic thoughts and feelings that come in the course of research. Things that aren’t exactly intellectual so much as visceral, the ideas that live in the small of your gut, or lodged in your throat. Think of them as the academic’s version of intrusive thoughts.

It’s harder to pass as a trans woman today than it used it to be.

That doesn’t sound so bad on first blush. But it has a few knotty corollaries. First, so much of the new latitude of everyone else’s gender positions—your deliberately clashing nonbinary visibility, your I-don’t-owe-you-androgyny, and so on—is premised on the heightened abjection of trans womanhood.

And second, how in the hell did those clocky bitches get away with it in the 1950s?!

I have a little obsession with transvestites. Before the glamorous transsexuals of yesteryear began to hoard all the attention, transvestites and street queens ruled the gay world, though they rarely got the credit they were due. Tall, broad, loud and unapologetic, in the days where hormones were new on the scene and surgeries the stuff of fantasy trips overseas, transvestites and queens were the signal trans women who held court in the bars and parks, took care of everyone by sharing housing, food, and makeup, and braved their scorn and misogyny for it.

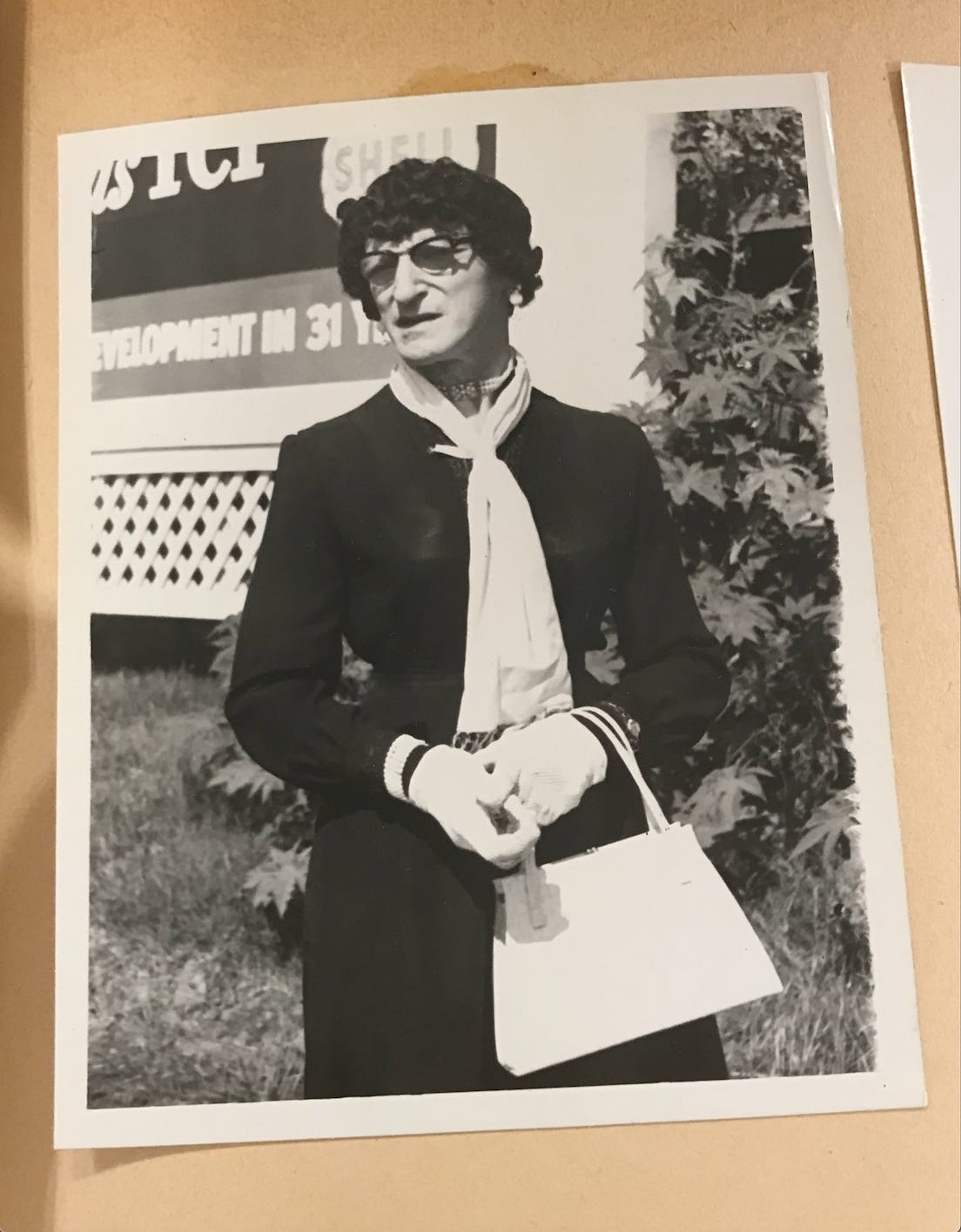

But something has always nagged at me in the mid twentieth century archive of transvestites. In letter after letter, story after story, and document after document, these women without access to medical transition gush about passing. Making it on the street, in women’s department stores, holding down jobs, and even dating, all without anyone ever catching on. Sure, they do have the occasional story about being caught, but the prevailing attitude is noticeably triumphant. And occasionally I’d come across a photo or two of them dressed in their finest and I’d think, okay, I know I have a trained eye of all people, but she’s clocky as hell. What gives?

Now do you see what I mean about being impolitic?

I don’t exactly feel good about thinking things like that. After all, not passing has become some kind of political virtue these days. Once again tying trans women’s value to what we can do for cis audiences, it’s supposedly a good thing to be clocked, like it proves you really mean it—being trans. Never mind that it’s usually white people, or trans people who have never had the experience of being turned inside out trying to get hormones and surgery, or losing their job or apartment for inconsistencies of name and ID, who make such pronouncements. In the neoliberal pageantry that is so much trans and nonbinary “radicalism” today, where having an interior identity so unique no one could ever understand it is highly prized, it’s become a little passé to want to be seen and recognized in a shared category like woman.

But that’s not what prompted my shame. It was that I had read my transvestite sisters of yesteryear, that I had seen them as not-passing. That’s the truth about passing that we’ve forgotten. It’s not a choice you make, to pass or not pass. Passing is relational, not an achievement; it’s way that gender is given to you (or withheld) by strangers every damn day, as Andrea Long Chu puts it so well. So why am I so given to scrutinizing the few visuals I find of the girls in the archive? Why do we read and clock each other so insistently and, sometimes, aggressively?

I find the concept of “internalized trans misogyny” simply not interesting enough to answer the question. With its psychologizing frame, it suggests a personal failure, a lack of integrity at keeping the badness of your culture outside you, separate from who you really are. Frankly, I don’t buy that. We don’t just internalize things like trans misogyny or racism, we are made of them, flesh and blood. They materialize us in the world before we could ever fantasize we have an interior identity all separate and protected.

A better answer might lie in a brilliant moment in the documentary Disclosure (dir. Sam Feder, 2020), where Candis Cayne is discussing her network TV history-making appearance on Dirty Sexy Money in 2007. Hosting a watch party at home with friends for her first episode, she remembers that everyone cheered and clapped when she appeared on screen. “And then my first line,” Cayne explains, “they lowered it two octaves.” Everyone in her living room went quiet at hearing her edited voice. “It was the most horrifying thing ever. They did it for one line to get to the idea that Carmelita was a trans woman.”

The editing to forcibly clock Cayne’s character is a reminder that visibility is not just a quantitative matter of being seen more frequently; visibility is a product of the medium, of the construction of trans women for consumption by an audience. Passing or being clocked is a product of the media through which you are seen, more so than the fact of being seen. And there is a pedagogy to the technology of visibility. As Angelica Ross puts it brilliantly in Framing Agnes (dir. Chase Joynt, 2022):

“It's like this kid holding a magnifying glass over an ant and burning it…we burn up under that spotlight. When you're in the hood and now they know how to look for trans people and what to look for…all eyes are on you and it's not always a good feeling.”

As our culture has become more and more fixated on trans women’s hypervisibility, we have taught people how to look out for us, how to scrutinize our bodies, and how to train a paranoid eye on every instance of femininity. When I look back at the pop icons of the 1980s or my childhood in the 1990s, I’m always struck by how clocky and sometimes straight-up brick high femininity was. Today, the irony is that many cis women celebrities (I’m looking at you, Kim K) obviously steal their aesthetic from Black and brown trans womanhood, exaggerating their femininity or sculpting their bodies to look far more trans than the referent that they bury. Trans women themselves haven’t benefitted from that process. On the contrary, it has made passing an even more difficult bar to strive for in everyday life.

I found it a little nerve-wracking to watch myself on screen in Framing Agnes, as thrilled as I was that the world was finally getting to travel with its brilliant cast of stars. On the one hand, to be in hair and makeup and lit and framed and edited by a trans team felt like the highest honor; on the other hand, I still wondered how the angles of my face, or my voice, would translate onto the screen. Such is the risk and reward of being seen, the way that trans misogyny constructs the very world in which we have to sink or swim.

One of the lessons of Framing Agnes is that we are far too presumptuous in thinking that we have it better today than people did in the 1950s, or that we can see their lives and struggles clearly from our vantage point, looking back. Most of trans people’s history exceeds our comprehension, no matter how rigorously we research and how carefully we tell their stories. We weren’t there and we are jaded by our own times. In that way, the past doesn’t belong to us. And the film makes the point that this is a good thing. When we wind back the clock to the mid-century and find that for many transvestites, putting on a sensible suit, a pair of pumps, a lace front wig and a face of makeup was enough for them to travel through the world without being seen as anything remarkable, it says a lot about what’s broken in our times.

fuck this is good one, I like feel it so much.

This was a really interesting and engaging piece, thank you. I am a white non-binary transfem with good access to healthcare, housing and employment so I did feel read by (and agree with) your comments around not passing becoming a political virtue, to an extent.

I would add that I think an element of the movement to reject passing is the consequence of exactly the phenomenon you are identifying — for me, transitioning at 27 means that passing feels unachievable, especially in the current environment. I have transfem friends who want to pass but don't feel like it's possible and consequently do not take any steps towards medical transition (why try if it's impossible?).

Also, for some reason, trying to pass feels more dangerous. Being perceived as an inner-city lefty enby hipster feels safer than being perceived as a trans woman. Race and class is intrinsically entwined in that.

Ultimately I haven't felt the space in my mind to consider passing and whether I want it. It's easier to not try. Instead I have tried to take ownership of not passing.