To be female is to let someone else do your desiring for you, at your own expense.

—Andrea Long Chu, Females

JUNE HAS COME a few weeks early on Twitter this year. Our cursed friend “Pride discourse” is once again in the melodrama of a full swing. Between now and the end of June I’ll be bringing you this series on trans pessimism that, I hope, leads us in other directions than becoming the Queer Sex Police of the NYPD’s dreams. To inaugurate the series, I have a question for the revisionism attached to the Stonewall riots: why is trans politics so fucking optimistic?

Lauren Berlant handily defines optimism in terms of attachment. In this idiom, optimism is “the force that moves you out of yourself and into the world in order to bring closer the satisfying something that you cannot generate on your own but sense in the wake of a person, a way of life, an object, project, or scene” (1-2, emphasis in original). Sounds lovely, but of course the eponymous concept of their book Cruel Optimism cues us into the ways that attachments to optimism often ironically incur and even prolong the very damage that they pretend to overcome. Optimism is a stubborn clinging to the scene of transcending the wear and tear of contemporary life that actually ensures its permanent exhaustion.

Sometimes I think we know this in our bones, but not our hearts.

If there was ever a concept for millennials and gen z, those for whom any fantasies of the capitalist and imperial good life in the global north have been set on fire by perpetual war, global financial catastrophes, the greatest uneven concentration of wealth in living memory, and the use of taxpayer dollars to underwrite apartheid in Palestine instead of canceling student debt, raising the minimum wage, and making healthcare and higher education public—well, you get it.

Trans optimism is an arguably cruel genre because there’s not much reason for trans people to be optimistic. Our meteoric rise only in cultural visibility has directly led to Caitlyn Jenner running for governor of California and shattered record after shattered record of violence against trans women of color. Over 100 bills in nearly 30 states have attempted to extinguish trans life in the first few months of this year alone by relentlessly targeting children. Despite the tiniest ameliorations in jurisprudence from our apparently bestest dude Neil Gorsuch and a metric ton of vapid symbolism (Kamala goes by she/her, PRONOUNS IN THE BIO!), this is an extremely dangerous time to be trans. And let’s be honest: it’s an okay time to be a white trans masculine person precisely because it is an extremely dangerous time to be a trans women or a trans person of color.

And yet if you look at the generic discourse that marshals us for the legendary month of June by lazily invoking words like legendary, you wouldn’t know it.

We’re instructed, no more than during Pride, to organize our lives in relation to political optimism, to live for a promised future of inclusion and freedom, or safety and care. A future where they stop killing us. A future that is paradoxically always just around the corner and yet guaranteed. But the tiring want of that future gets wrongly projected in reverse onto the present, when the point was supposed to be that we aren’t free now. And so, the description of present social life gets elevated to the political without cause. You’ve seen it a thousand times. The fact that a trans woman of color does something is celebrated as a political act. Except, the fact that any of us Black and brown girls survive to do some living tells us next to nothing. It’s mundane as shit. Revolution is something else, not a fact of life and not an act of living. Besides, the trans woman of color whose life is invoked is always putative. She’s no fact.

Who is she? How do you know her? I know why Chase Bank, or Sephora pretends to know her. But you? What’s your excuse?

Much of this optimistic attachment promises—magically, it would seem, which I can again excuse capitalists and their literal commodity fetishism for more than I can broke queers—to reverse the deadly forces that stalk trans women of color. This line of thinking ought to be tired. “My god, the revolution is finally here!” is attributed to Sylvia Rivera at the time of the Stonewall riots in 1969. We are living over five decades later and, with all due respect, there has been no revolution.

Let me be mean for a moment, but not because I am mean. I mean, let me be stylistically mean, in order to show, by contrast, how infantilizing and idealizing our commonplace rhetoric and figurations of Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson have become.

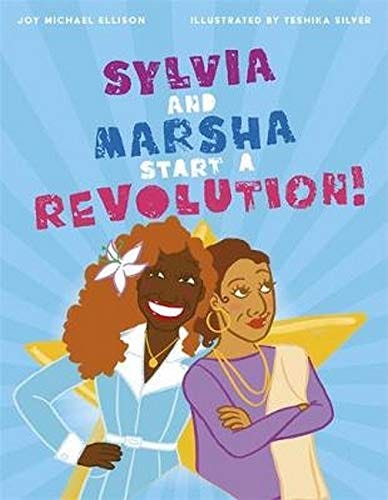

A children’s book is about as literal an example as I can offer you. Sylvia and Marsha Start a Revolution! tries about as hard as humanly possible to make what it says true without actually doing anything (a trait of optimism to add to our collection). Here is how one UK bookseller describes it: “A picture book telling the story of Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, the transgender women of colour who fought for LGBTQ+ equality.”

To be mean: no.

Rivera and Johnson most certainly did not “fight” for something called “LGBTQ+ equality,” nor does the contemporary phrase “transgender women of colour” recognize the rich and complex epistemologies of their race, gender, sexuality, language and political tactics. Indeed—and I truly hate to say this—some terfs who delight in creating right wing memes that they then bulk email to trans women like me have taken pleasure in claiming that Rivera and Johnson did not identify as trans women in one of their recent creations (I suppose they think this sleight of hand will convince people meme-etically that “trans politics” is really men taking over…from…also men? I don’t know, they’re not sending their best). Trans optimism is shockingly less sophisticated than terf warfare at the level of tactics, in case you needed proof that we’re way off course.

What pricks about Sylvia and Marsha Start a Revolution! is the astonishing hubris through which it uses them to project something onto our present that is plainly absent. Yes, they did start a revolutionary organization and they did support other revolutionary projects like the Black Panthers and the Young Lords, but the idea that we—the collective noun of the historical present—inherit this uninterrupted legacy, that we are somehow continuing their direct work, the “LGBTQ+ equality” and whatever else Pride is supposed to indicate in the liberal political imaginary, is historically laughable. This isn’t a history lesson, but to make the point: Black trans women continue, today, to do radical organizing on the left around prison abolition, police violence, housing, poverty and welfare, and mutual aid. As did Rivera and Johnson before them. But those are decidedly not the central platforms of “LGBTQ+” politics. Nor were they in 1970. And yet the use of Black trans women and trans women of color as their figureheads, the claim to work in their name, is everywhere.

This is the dirty work that optimism does.

And here comes the syllogism: if Black and brown trans women are always already the most oppressed and yet are also somehow living out the revolution at the same time, why are they not free? If the storyline is static about the last fifty years and we are just as unfree as ever despite having known how to free ourselves the whole time, the storyline is lying about something.

Are you starting to see why I’m a trans pessimist?

Whatever “trans” as an abstracted umbrella means these days, it is not Sylvia and Marsha starting a revolution.

ANDREA LONG CHU HAS has made perhaps the strongest argument for trans pessimism to counter this mendacious optimism. Its frequently misread brilliance is that it’s a universalizing argument: everyone “is female” because the female condition reveals the structural fallout of attachments to optimism. Don’t get it twisted, you are not biologically (literally) female, that’s some terfy nonsense. What Chu uses the concept of the female to demonstrate is that there is nothing peculiar about trans people’s failures to become what they desire to be, whether that desire be happiness or a vagina (oh, the ways in which people misread her New York Times essay). Given that trans womanhood is the most negated, most reviled, and most shameful form of gendered desire out there, she is right to lean on the example. In a culture that manifestly hates women on an unconscious level, trans women are the remarkable ones who dare to desire to become women despite knowing that desire can only ever deliver you to failure and condemnation. The thing is—and Chu embraces this better than most—there’s nothing actually that bad about desire’s inevitable failure to deliver.

That’s just, like, how desire works, female-dude.

Imagine wanting something you can’t ever have and choosing to strive for it anyways. That’s what every single person does, every single day, with every single thing they desire (though we do not have to admit that and can build all sorts of reactionary things to pretend otherwise). But trans women? We do it for fucking womanhood and so we are hated and envied for our desire to a degree that can prove fatal.

Chu is an avid reader of Berlant and her theory of trans femininity’s failed desire no doubt follows Berlant’s observation that “one of optimism’s ordinary pleasures is to induce conventionality, that place where appetites find a shape in the predictable comfort of the good life” (Cruel Optimism, 2). Cue here, no doubt, the thou doth protest too much chorus of brave gender warriors who proclaim that they don’t ever, under any circumstance, want to pass, and that somehow makes their queerness holier than thou, mortal transsexual woman. As Chu provocatively puts it (I’m obviously grumpy about the trans misogyny that animates most readings of her work, if by misogyny I mean violently ignoring genre to take her ideas literally, as if they were written in arithmetic—a repulsive male trait of reading, if ever there was one [See, I can do it too! Relax.]):

“The political is the sworn enemy of the female; politics begins, in every case, from the optimistic belief that another sex is possible. This is the root of all political consciousness: the dawning realization that one’s desires are not one’s own, that one has become a vehicle for someone else’s ego; in short, that one is female, but wishes it were not so.” (Females, 13, emphasis in original)

Chu here provides us with an operative reason to dislike trans optimism: it responds to a useful self-awareness with just about the dumbest doubling down possible on what caused the problem. Oh, trans feminine and racialized life are as abject as it gets, generically prohibited from becoming real according to the powers that be despite their self-evident realness—you’ll recall that Black and brown girls quite literally invented the category—?

No, you see, it’s actually the contrary: trans women of color show us the revolution, show us utopia in their suffering! We must make of them our models, our inspiration!

For the love of gay Hegel, please stop, your dialectic is giving me a headache.

A trans pessimism is deeply skeptical of any political project where trans signifies the exceptional or idealized, ready-made queer political programme or promise of utopia, through the outrageously impossible “revolutionary realness” of existing trans women of color’s living conditions.

Whatever world you are agitating for, ask yourself why it needs a Black trans woman as its prop, because unless we’re talking about Black trans women’s actual activism, the answer is probably that you’re stuck in the hamster wheel of optimism. (Whether trans pessimism might take a non-appropriative position on Afropessimism, a spacious field of Black philosophical critiques of modernity—with many worthwhile rejoinders from Black feminist, Black queer, and Black trans thinkers like Robert Reid-Pharr, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, C. Riley Snorton, and Che Gossett—remains unclear. I am alarmed at the degree to which unsurprisingly white trans and queer ideologues lift Black concepts with rich and often centuries-old genealogies and repackage them as cheap slogans with whitewashed politics—think only of “gender abolition,” which, I have to say, makes precisely zero sense in the way it is used. Show me how to abolish gender in a way that won’t be structurally trans misogynist and envision my literal obsolesce, and I’ll buy you a cocktail this June.)

Trans pessimism, for me, is not just a female trait, but one with a distinct consciousness about race. It’s an indictment of the world as arranged, a world whose modernity is the transactional outcome of the transatlantic slave trade, global colonialism, and settler colonialism: three racialized processes of political and economic domination that directly birthed the Western sex binary and, much later, gender—two of its prized enforcers. Like it or not, single-axis politics like trans optimism operate within that worldview and so find themselves unable to bring about anything worthy of the word revolutionary.

While many rejoice at their obsessive incantation of Rivera and Johnson’s names this June, the countless Black and brown trans women who have found the secret to surviving in this world will remain just as faceless to the proud as they were in 1973 when Rivera had to physically fight her way on stage in Washington Square park to address the increasingly gender-normative, predominately white gay liberation movement. Until that changes, don’t bother trying to sell me your optimism.

Part II in this series, “The Tragedy of Homosexuality,” will appear in a few weeks. Subscribe to Sad Brown Girl to make sure you don’t miss out! Paid subscriptions help me get closer to facial feminization surgery.