When I Reclaim My Spirit, I Am Not Your Tragedy

For the love of femininity and against the spectacle of trans women and children's suffering.

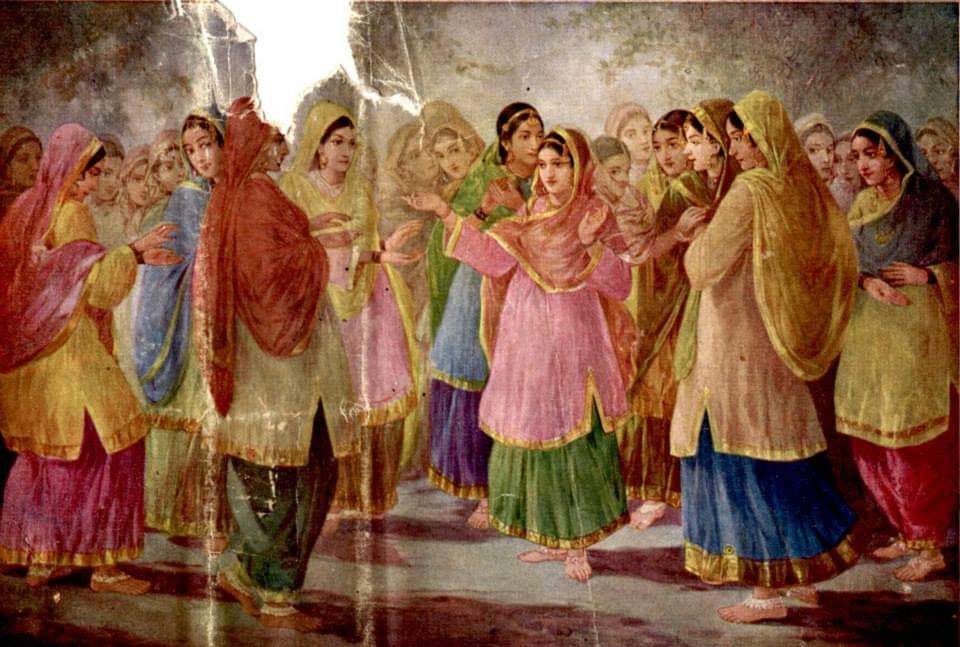

When I was young, before I could name the strange feeling that structured my exhausting little life, I was embarrassingly afraid of femininity. As a child I would watch in ravenous envy whenever the women in my family gathered to dance giddha before a wedding—one of the few times I witnessed the stoic Punjabi women who raised me camping it up, unafraid to be feminine. Decades later, in Brooklyn, I would feel like a child again watching Black and brown femme queens own a very different kind of dance floor. Their awesome embodied fluidity in both cases was an alchemy of flesh and some force I didn’t recognize. It felt like a threat as much as it mesmerized me, though I didn’t understand why at either age. Whatever it may have been, I was sure femininity was too powerful for my frail, untransitioned body. I spent years wondering how femmes of any gender could dance, walk, and move through the world with a daring that seemed a different species than my rigid, lanky profile. I barely had my two feet pressed into the earth, but femmes seemed to fly through the air.

It’s taken me many years to understand that the special force added to the flesh in high femininity is spiritual. That trans femininity, therefore, is not a passive identity, but the outcome of spiritual process of transubstantiation: making one lowly substance (a body first recorded as male) into the most exalted of states (resplendent womanhood). This is true even for non-trans femmes. The art of appearances that is high femininity is the very opposite of superficial, which is no doubt why it is so hated. To be seen in shades of glamour and femme finery is to risk so very much in a world of scarcity and resentment. The femme, like the faggot, is the one who simply cannot conceal her majesty and will not be shamed. The femme is willing to be and be public—defiant and unapologetic because she has no choice.

Part of the cunning trap of the surge in anti-trans political violence over the past few years has been its spiritual immiseration. When you weave a moral panic, you substitute for reality an invented fantasy. Often it is one that perverts reality to satisfy deeply rooted anxious and aggressive feelings about how the world really is. This is why so much transphobia is made up of hypothetical scenarios and easily falsifiable claims. Grandiose What Ifs and What Abouts replace what is actually happening and disavow who is actually in power and responsible for harm. As social media and print journalism have become obsessed with these fictions, they have rationalized the absurd situation where politicians can write laws targeting, say, four children in the state of Utah as if they were a serious public danger, or can ban the surgical sterilization of kids that doesn’t actually occur except when it is forced on intersex children, who will not be spared. Anti-trans political violence uses moral pretense because it is an ideological organ in the procedure of class warfare: shrinking the state’s investment in redistributing the resources of life while amplifying its role as the police. If you take away, say, access to health care and the legal concept of rights held in the body by claiming the harm is meant to protect us from a dangerous and immoral minority, the slide towards material misery is much easier to popularize.

But we have neglected the attack on the spiritual significance and value of trans life that will not be moralized in bad faith or into oblivion. The targeting of trans kids, like the violence directed at Black and brown trans women, arrives primarily clothed in the genre of tragedy. We are asked to secure the flesh, the bare life of trans people, whose deaths are supposed to be our only motive. We cannot let more kids, or more trans women of color, die.

And surely we cannot. Yet so we do, collectively, every damned day.

The tragedy befalling the trans flesh has yet to prove a successful motive for actually stoping or overturning the tide of anti-trans violence. Perhaps we have misplaced our faith. Perhaps we are actually all invested in the spectacular suffering of trans people, especially women and children, and perhaps we are satisfied with that suffering more than we care to confess. Perhaps we covertly believe in the tragedy of trans people because we take a dark satisfaction in how the trans fall from grace might reveal the sinfulness of this world.

That, I would simply say, is an unacceptable sacrifice.

However secular we might think ourselves, the tragedy genre is still organized in deeply messianic terms. Even in the Western queer and trans imaginary. Tragedy, that very Christian narrative of the predestined fall from grace, creates a difficult narrative situation for politics. Tragedy can only be remedied by redemption, as when Christ, who bore the cross of the human world of sin, comes again but with the full force of God. And indeed, the idealization of trans women and children today has that messianic quality to it. If only we celebrate Saint Sylvia and Saint Marsha properly, the second coming of the trans women of color of Stonewall will redeem us all. If only we learn to protect trans children to save them from suicide, their pure innocence will redeem us from the harm we have inflected on them. Our politics will be saved by invoking trans women of color, or children, and acting in their name. We will rescue them from their betrayal by idealizing them.

At its root, the redemption of tragedy requires waiting for the creation of a new world, a heaven on earth. The second coming requires waiting for utopia in the next life, which is why I don’t subscribe to often-celebrated queer utopianism. The spiritual cry of the femme, as I have come to understand it, is unconvinced by the promise of waiting out this sinful world. She urges us to fight now, here on this earth. Her aim is to transform what is already here, instead of hoping that one day the world will be redeemed from without, by a higher being. That is the legacy that Sylvia and Marsha left us. Not instructions to deify them and await their second coming.

We must let the dead rest instead of expecting them to save our mortal realm.

As we confront the unprecedented scale of anti-trans political violence today, I ask us to consider that we are doing a disservice when we frame transness in the moralized terms of tragedy and redemption. When we attend only to saving trans people’s lives, we inadvertently agree with our oppressors that the spiritual matter of the quality of that life is irrelevant.

The care of the spirit is the sacred work that trans feminine people most of all have kept alive for centuries. It was, therefore, some of the first spiritual work targeted by colonial gender violence, as when the Spanish, French, Portuguese and English singled out two-spirit people as part of their genocide in the Americas, or when the British in India targeted hijras for eradication on the ground that they were spiritually and sexually immoral. The continued impoverishment of these incommensurable forms of spirit is part of the suffering that we are still experiencing today, albeit in different circumstances. But when we reclaim the spirit, and name our culturally distinct trans ways of life not as mere acceptable forms of flesh, but spiritually valuable gifts, we may yet find stronger grounds than we have had to date.

The fact that trans femininity, for one, is often larger than life, that it transforms the flesh from one form to another by imbuing the mortal coil of the body with exalted beauty, is part of why trans misogyny is so ubiquitous. The hatred of femininity, after all, is a signature marker of Western culture. Before you next frame your opposition to legislation through only the specter of suicide, or before you spend time trying to debunk the moral panics libeling trans women and girls online, I invited you to consider something. Imagine the force of a trans feminism that wasn’t merely trans-inclusive regular feminism, but actually did what most liberal feminism has refused to for centuries: desire and love femininity. The world built by that feminism would surely have been one in which a young Jules would have been instructed in valuing the magical force she first saw in the ecstatic dancing bodies of her kinfolk, instead of fearing it.

That, too, is worth fighting for.

amen!

when you link a book can you link a PDF or download of it instead? I don't think most of us have institutional access.