The Logic of Protection

The fantasy that love is enough shrinks pro-trans politics down to nothing.

I.

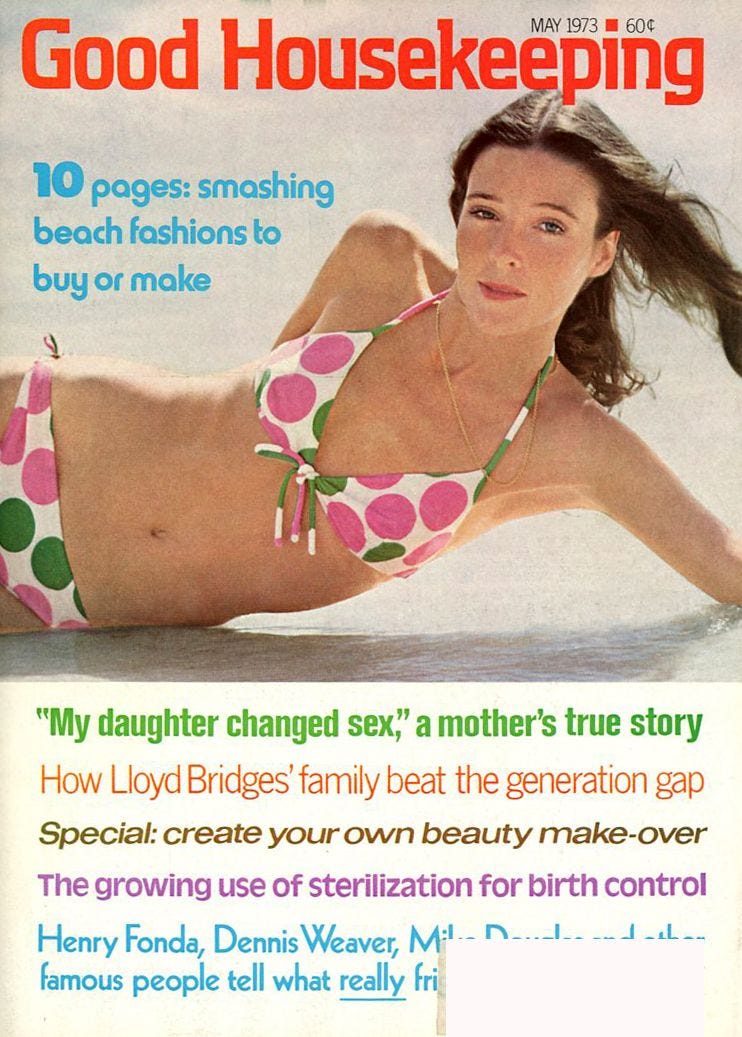

In 1973, Good Housekeeping published “My Daughter Changed Sex,” an anonymous article written by the mother of a trans man in his early twenties. The story went just about how you might imagine. The author recounts the “22 years of tragedy and misery” it took for “the boy inside” her son, who she calls “Tracy” in the article, “to emerge.” Her son was “a tomboy” from infancy and his masculinity was met with alarm by both her and her husband, Jim. Trips to a pediatrician, school nurse, and psychologist convinced the parents only that they were doing something wrong reflected back in their child’s masculinity. After graduating high school, the son moved far away for college and more or less stopped speaking with his parents. A year and a half later, he returned home to tell his parents that he was a man and that he had decided to medically transition.

The mother shares that she and her husband were overwhelmed by the news, unsure what to make of the word “transsexual.” But their son explained the great pains taken at the gender clinic in which he had enrolled: “grueling physical and psychological” assessments in which he was “interviewed, probed, poked, examined, cross-examined” over and over. Of fifty-four applicants, he was one of two who passed muster and was permitted to start testosterone. After another full year of paying for psychiatric supervision of every detail of his life to ensure he was living by the clinic’s definition of a rehabilitated man—the infamous “real life test”—he had come to see his parents for a specific reason. The gender clinic “insisted on the permission of at least one member of the patient’s family” to approve surgery. He was a legal adult, but the clinic imposed this obstacle on patients intentionally to make it even more difficult to obtain surgery.

The mother pauses at this point to ask for empathy from Good Housekeeping’s readers about the decision facing her. “That’s how it came about that a fairly average American couple sat in a fairly average living room trying to hold on to their sanity as their daughter told them she was in the process of becoming a man.” She recounts that “I tried to study Tracy as if from a great distance, as if she were a stranger, and I had to admit that, had I really not known her, I would have assumed she was a young man.” But it was, in the end, the “indescribable sadness” in her son’s eyes that persuaded her to give the surgery her blessing. She and her husband could have objected, “but Tracy was our child, after all, and love for a child can triumph over bitterness and estrangement. I looked at my husband and knew that he was thinking the same thing. There really was no alternative for us but to accept—him.”

The article shifts around the pronoun him. Not only does it signal the mother’s emotional conversion, but she grows increasingly confident having used the word, reciting nearly a thousand words on the scientific and medical legitimacy of transsexualism for her reader’s benefit. Although the subject is “controversial,” she admits, a long list of specialists from elite research universities buttress the rightness of her agreement to her son’s surgery. Various theories for what make people transsexual and explanations for why hormones and surgery are sometimes acceptable for them after exhaustive screening are rehearsed for a Good Housekeeping audience. The mother plays the role of the reasonable, but reluctant convert who can be trusted. (She was especially surprised to find out, for instance, that chromosomes do not genetically determine whether someone becomes a man or woman.)

After indulging in a long rendition of her son’s surgery, the mother finally relishes in his middle-class success as proof that she was right to have given her consent. He was now happy, a dramatic change from lifelong depression. But perhaps more importantly, given the list that follows: “he has a good job during the day as a salesman”; “he attends college at night” and is “talking about going to medical school”; and “to our astonishment,” he “has had great success with girls.” It turns out that the parents were wrong to doubt that having a trans son would be different than having a daughter. To emphasize this point to the readers of Good Housekeeping, the mother ends her essay with gratitude. “I have another reason for laying bare all the misery and anger, the frustrations and fears that Jim and I and Tracy and Daisy”—the son’s girlfriend—“have lived through. It is to pay tribute to the remarkable men and women who have helped us find our way out of the darkness. Their selflessness, courage and compassion have shown me there is no limit to what human beings, at their best, can accomplish.”

She was speaking, of course, of “selfless,” “courageous,” and “compassionate” doctors and psychiatrists. It was a remarkable statement given how demonstrably punitive the gender clinic in which her son had enrolled was, rejecting 94% of people who walked through its doors during the same period as him. But what was for fifty-two other people a failure, was for her family a triumph.

This is the logic of trans protection: love your trans child, partner, friend, co-worker, or whomever else you know. Trust in the system, no matter what it does to the trans people you don’t know. And share your disappointment, ambivalence, and initial rejection of the trans person in your life, for your honesty will be rewarded not just for its courage, but in its deliverance by a higher authority: the doctors, scientists, and psychiatrists whose new custodianship over the trans person in your life affirms your own. In the end, nothing really has to change.

I imagine that this article reads poorly in 2024, but I offer it precisely because I think very little has changed since 1973. I’ll put this to you now, though I will work my way up to the conclusion in what follows: protection remains, fifty years after Good Housekeeping printed its blueprint, the primary sanctioned defense of trans people and transition, especially for youth. But protection’s legacy is so disastrous that continuing to replicate it without any evidence of success is unnacetpable. I will try to explain why it remains so difficult to give up.

II.

“My Daughter Changed Sex” was enthusiastically received by liberal trans organizations, particularly those attempting to build leverage within the medical establishment and lay the groundwork for private transgender civil rights. The article was put into reprint by the Erickson Educational Foundation (privately funded by trans businessman Reed Erickson) and it became a frequent reading recommendation.1 In 1978, the parent of a 16-year-old trans boy wrote to Gender Review, a newsletter printed by the Foundation for the Advancement of Canadian Transsexuals (FACT), expressing reservations about her son’s request for surgery. “Yes, it appears that a fair number of parents entertain feelings of moral confusion and doubt, and often, personal guilt or even a sense of insecurity about their own gender feelings and behavior when confronted with their TS [transsexual] child,” replied the editor. To address the confusion, he recommended involving experts. “A psychiatrist, psychologist, endocrinologist and/or other professional specializing in gender problems should be sought for evaluation.” Once armed with expert knowledge, “only you can resolve your ethical dilemma,” continued the editor, “which may be accomplished by means of objective detachment, on the one hand, viewing/assessing your daughter as possibly of a group of unfortunate individuals who require appropriate medical treatment, and on the other hand, giving your child all your loving care, empathy and support in this very difficult period of both of your lives.”2

The marriage between the tragedy of a child who spoils the family and the mercy of medical reason to treat it is much more popular today, mostly because it was also put forward as the best way to accept lesbian and gay children in the 1990s and 2000s. (In that case, psychologists played the role of reassuring parents that lesbian and gay people were not inherently deviant and could grow up to behave normally. Today they can even get married). It’s worth noting, however, that this narrative also existed for trans youth fifty years ago. This matters because trans youth are today, unlike in the 1970s, the subject of a staggering media and political spectacle. Political attacks on medical transition have proceeded systematically by singling out youth first, banking on the proposition that a medically transitioning teenager is utterly new and untrustworthy.

I have patiently explained the fraudulence of the claim that youth transition is new for many years. Yet I continue to notice how easily the fantasy that trans youth were invented by doctors (or, for the more conspiratorial set, by the internet, peer pressure, or some other magical force) grants impunity to regressive proposals, as if they were humane, nuanced, and non-ideological, free of the passion and bias that discredit “trans activists.” In the recently released Cass Review on transition services for youth in the United Kingdom, for instance, the report claims that “services for children and young people with gender incongruence started in the mid-1970s in Canada, and in 1987 in the Netherlands” (p. 67).3 This is patently false. As Histories of the Transgender Child details at length, teenagers medically transitioned in formal clinics like the University of California, Los Angeles as early as the 1960s. They also did so in every region of the United States through private physicians and surgeons. The first gender clinics the likes of which we still have today, which opened in the 1960s, were in fact primarily concerned with a population of street youth that included teenaged trans girls in cities like San Francisco and, perhaps to the dismay of the Cass report, London.4 In 1969, Antony Grey, a famous homophile reformer, wrote to a comparatively unknown trans woman working in social services in San Francisco named Wendy Kohler. Grey sought her advice on how to approach the teenaged trans women “in SoHo and other parts of central London” for whom he was hoping to build a service and medical pipeline through “the Westminster Council of Social Service,” which was pursuing a “working party” on the needs of urban youth.5

Still, there is no objective amount of time ago for something to have happened that confers on the people associated with it agreed-upon legitimacy. And misrepresenting history is only the tip of the iceberg of the Cass Review’s twists and turns. But it is also a fantastic example of why invoking science and medicine to legitimize transition is a losing strategy. It is profoundly easy for a motivated author to tell a decontextualized story of medical transition in which youth transition is very recent, the gold standards of evidence-based data are lacking, and in which a “challenging public debate” (p. 12) should result in sober compromise to prove the wisdom of those in power. The conclusion—that it would be better not to allow young people to have the bodies they want—is successful partly because almost no one has the subject-area expertise to pick it apart, let alone provide a pile of counter-evidence. Even those who do, like the physicians, psychiatrist, psychologists, and surgeons, not to mention major medical associations, fail to make a difference. Much like with the science of climate change or vaccination, the defense of scientific authority against its supposedly irrational or unfairly political critics misunderstands that scientific and medical consensus is itself the outcome of a political struggle over the truth.

One reason I am not surprised there has been no mass movement in solidarity with trans youth or adults is that the message from big advocacy organizations, with few exceptions, has been anti-political: Let doctors and studies speak for you in courtrooms or state legislatures. Do not act hastily or demand too much, like unconditional permission to transition, even if you are an adult. Be reasonable, wait on reason to do its job, and do not rock the boat too much. You may protect the trans people in your life, and protect yourself, but nothing more is required.

III.

Earlier this month, Maryland’s legislature passed the Trans Shield Act, which prohibits states that have banned medical transition from pursuing claims on Maryland healthcare providers. The bill would have the effect of indirectly “shielding” people traveling from out of state for transition-related services by prohibiting legal action against their doctors and clinics. The bill, which awaits the Governor’s signature, is similar to a state law protecting abortion providers adopted last year, and Maryland would be the twelfth state to enact a shield law for medical transition. Its logic is a symptom of the legal and administrative fragmentation of the United States along the axis of medical procedures.6

The shield law is smart in its narrow context, but its limitations are obvious: the law protects doctors and medical clinics, not trans people or transition. The trans people who would be indirectly protected by the law are only those who have the means to travel to Maryland for healthcare that they can already afford, or those who can relocate to do the same. The state would only confer private, contingent rights to individuals who can claim them in the private healthcare market, not collective or genuine access to medical transition. This matters most for young people, since minors rely entirely on their parents or guardians to make decisions for them about healthcare. The national future of medical transition, meanwhile, is up in the air. It is unclear what the Supreme Court might rule on state bans. But were a national ban on medical transition passed by a future Congress, or a future Supreme Court ruling came to a similar determination, state shield laws would offer no resistance.

Protection is the most conservative way to guarantee something. It is a defensive strategy that aims for the smallest scale of victory possible. Even if some forms of protection, like state shield laws, serve a useful purpose right now, the broader politics of protecting trans children is likely to fail dramatically. In fact, it has already failed, over and over in every single state that has passed a ban on medical transition for youth despite the testimony of parents and doctors that the state should not intrude on the private right of adults to make medical decisions for children. That may be a necessary legal strategy in a courtroom, yet it seems to be the most popular strategy of all.

GLAAD’s ‘Protect this Kid’ campaign debuted earlier this month. The initiative invites people to “change the narrative” around child protection, presumably through posting on social media. The “protect our children” slogan greasing right-wing political violence, claims GLAAD, “is being used to create a false narrative” that can be corrected with the proper information and the right emotional appeal. Through the motif of photographs of gay and trans adults as children, appearing both cute and vulnerable, GLAAD proposes that it is “reclaiming this language on behalf of people who actually need protection right now—the LGBTQ community.”7

As should be clear by now, this isn’t an original claim. The identical argument was made in Good Housekeeping, but it was also reiterated after the murder of Brandon Teena in the 1990s, and yet again through the specter of gay teen suicide in the “It Gets Better Project” of the 2010s. Most recently, trans youth have been narrated as at risk of depression and suicide if they are not protected by parents and doctors.

What is striking is that after fifty years of saying we should protect gay and trans youth, the claim has simply failed to do so. Political homophobia and transphobia targeting youth are arguably more prevalent today than in any prior moment in US history.

There is also an underside to the proposition that the discourse of child protection, which libels gay men and trans women as sex criminals deserving imprisonment or, in extremist articulations, death, could be, or should be, “reclaimed.” It is a slap in the face to everyone who has been relentlessly targeted by child protection fanatics to claim that adopting that very rhetoric will not inflate its circulation and power. The history of “child protection” in the United States is a litany of racist and, in some cases, openly genocidal state projects: the removal of Indigenous children from their kinship networks for abuse in the residential school system; the creation of what Dorothy Roberts calls “family policing,” through which the federal government and state governments have waged political war on the Black family by calling it child welfare; and the child separation policy practiced by US immigration officials.8

GLAAD, like so many others before them, asks that we protect the trans child inside the private family. But to so restrict our concern, to shrink the scale of politics down to the size of a private family, is to avoid the obvious: that the family might not be the best place for children. It is remarkable, paying attention to the content of arguments for protection, how often they display an open dislike of children. The Good Housekeeping mother did not provide a happy family environment for her son. On the contrary, she retained the incredible power to sign off on his body into his adulthood because the gender clinic affirmed her authority as rightful. In 2021, when Missouri was considering an anti-trans bill, Brandon Boulware went viral for emotional testimony to state lawmakers that the ACLU promoted as a call to action. His testimony, however, was not much nicer than the message in Good Housekeeping fifty years prior:

“I’m a lifelong Missourian. I’m a business lawyer. I’m a Christian. I’m the son of a Methodist minister. I’m a husband. I’m the father of four kids, two boys, two girls, including a wonderful and beautiful transgender daughter.

[…]One thing I often hear when transgender issues are discussed is I don’t get it. I don’t understand…I didn’t get it either for years. I would not let my daughter wear girl clothes. I did not let her play with girl toys. I forced my daughter to wear boy clothes and get short haircuts and play on boys’ sports teams. Why did I do this? To protect my child.

[…]

My child was miserable. I cannot overstate that she was absolutely miserable. Especially at school. No confidence, no friends, no laughter. I can honestly say this, I had a child who did not smile. We did that for years.”9

Boulware’s conversion came one day when her daughter had “sneaked on one of her older sister’s play dresses and they wanted to go across the street and play with the neighbor’s kids.” It was dinnertime, so Boulware replied “no” and saw his daughter recoil. Misunderstanding his reasoning, she asked him if she would have to put on boy’s clothes to go and play. “It’s then that it hit me,” testified Boulware, “that my daughter was equating being good with being someone else. I was teaching her to deny who she is. As a parent, the one thing we cannot do is silence our child’s spirit. And so, on that day my wife and I stopped silencing our child’s spirit.” Now, Boulware reported to the legislative committee, he had “a confident, smiling, happy daughter. She plays on a girls’ volleyball team. She has friendships. She’s a kid.”

It’s astonishing how much confessed cruelty is played as inspiring because Boulware eventually had a change of heart and, crucially, now wanted to stop Missouri from dictating decisions about his daughter’s life that were his to make. The discourse of protection made absolutely clear who was really to be protected: a father. His daughter had convinced him of her worthiness after enduring years of suffering at his hands, and now that he loved her, the state should not intercede, presumably just as it shoud not have interceded when, by his own admission, he made her miserable.

Boulware’s story likely became popular because it distracted from the more grisly question of what happens to all the trans girls whose parents don’t have a change of heart. In the logic of protection, which is fundamental to the politics of trans inclusion, the trans child who is mistreated, neglected, abused, or harmed must convince the people with power over her that she deserves to be loved. If she does, she can then be accepted because she has repaired the damage her existence caused, an obligation certified by the negative reactions and behavior of adults. The logic of protection preserves the private family, much as it preserves the power of medical experts, because it seeks to contain and control trans people. It is a ghastly proposition that chills my bones every single time. Imagine: a twenty-two-year-old man must come home to ask his parents to consent to his surgery. Imagine: a school-aged girl must convince her father she deserves his love.

Protection is a desperate attempt to produce the veneer of trans inclusion as progress while avoiding the genuine challenge of letting trans people transition simply because that is what they want. The logic of protection is not new, but it is today proving its ultimate futility. It not only fails to stop the restriction of medical transition because it has no collective vision or demand, just a series of private individuals upon whom the state shall not infringe (until it inevitably does). Worse, protecting trans people only if they repair the private family, and only if they submit to the authority of medicine, offers an uncompelling cause to fight for.

Who, exactly, wants to march for the power of a psychiatrist to decide if a stranger deserves his own body? Who, exactly, wants to march for the right of parents to harm their kid until she convinces them that she can make the family whole again? As Sophie Lewis or Max Fox—who have each written incisive analyses of the moral panic over trans youth and the farce of child protection that you should read—might put it: In saying we wish to protect trans children, we lie to them, and we lie to ourselves. We are really protecting ourselves (adults) from what children ask of us. We are protecting the primary systems that exploit and abuse young people by calling them care (medicine, yes, but also the child welfare system, the school system, the mass incarceration system, and their companion, the private family). There is a fantasy of repair run amok in protection and a scandalous dismissal of the material needs of trans people. The costs of that fantasy, I submit, were already intolerable fifty years ago. What does it say about us that we don’t sound all that different about transition today than Good Housekeeping did in 1973?

Erickson Educational Foundation, “My Daughter Changed Sex” (reprint from Good Housekeeping), circa 1970s, International Gay Information Center ephemera files, Box 4, New York Public Library, New York.

"Family Forum,” Gender Review: The FACTual Newsletter 1, no. 1 (June 1978): 9.

https://cass.independent-review.uk/home/publications/final-report/.

Jules Gill-Peterson, Histories of the Transgender Child (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 129-162.

Antony Grey to Wendy Kohler, December 11, 1969, Hall-Carpenter Papers, Box 11, Folder 19, London School of Economics and Political Science Library, London.

"Md. poised to became a trans santctuary state,” The Washington Blade, Aporil 6, 2024, https://www.washingtonblade.com/2024/04/06/md-poised-to-become-trans-sanctuary-state/.

https://glaad.org/protect-this-kid/

Mary Zaborskis, Queer Childhoods: Institutional Futures of Indigeneity, Race, and Disability (NYU: New York University Press, 2024); Dorothy Roberts, “Building a World Without Family Policing,” LPE Project, July 17, 2023, https://lpeproject.org/blog/building-a-world-without-family-policing/; and Southern Poverty Law Center, “Family Separation: A Timeline,” March 23, 2022, https://www.splcenter.org/news/2022/03/23/family-separation-timeline.

Joe Millitzer, “Missouri dad goes viral after emotional testimony on transgender daughter and sports,” Fox 2 Now, March 18, 2021, https://fox2now.com/news/missouri/missouri-dad-goes-viral-after-emotional-testimony-on-transgender-daughter-and-sports/.

I am going to commit the cardinal sin of commenting on an old post because this article is the reason I decided to subscribe to your newsletter today. Something I have said in discussion with other trans people but that is not always appreciated, unfortunately, is that, while it is great that there is supporting evidence that transitioning benefits trans people, all of that wouldn't really be necessary if we did not already suffer from the prior injustice of being deemed unfit to speak for ourselves. A trans person's right to transition, whether or not you think it benefits them, should be respected in the first place. End of story. What would a world in which we are not dependent on doctors who are at best ignorant of and at worst hostile to our needs look like? I, for one, am very keen on finding out some day.

Hi Jules! I agree with all of your arguments. Do you have any suggestions for alternative suggestions? "Uplift Trans Youth"? "Liberate Trans Youth"? Something else?